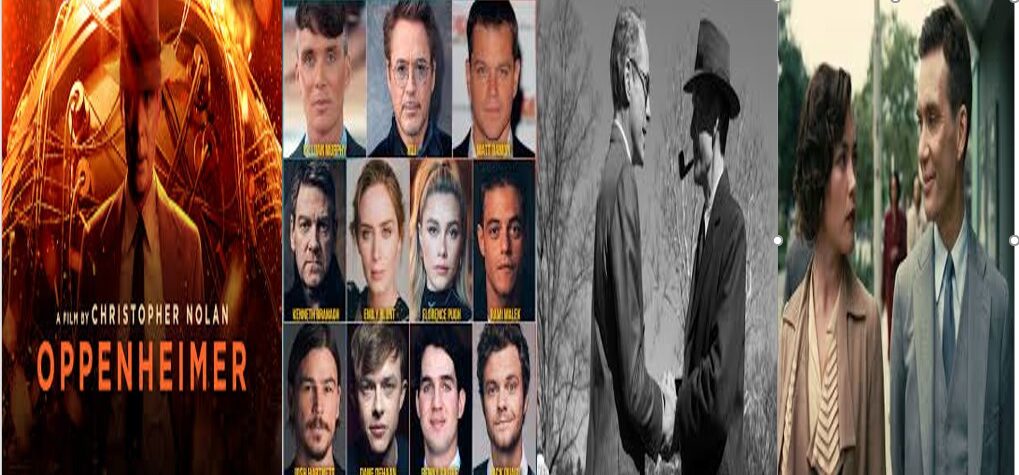

The 96th Academy Awards showered trophies to one of the most brilliantly made film of 2023 , Oppenheimer. We will provide a detailed review of this film which will justify why it deserved to win big at Oscars.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” is portrayed in Christopher Nolan’s nuanced, realistic manner, which is a masterful formal and thematic triumph.

In three eerie hours, Christopher Nolan’s monumental picture “Oppenheimer,” which tells the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, dubbed “the father of the atomic bomb,” compresses a monumental transformation in human consciousness.

Masterful Depiction

It masterfully depicts the turbulent life of the American theoretical physicist who assisted in the research and development of the two atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II — cataclysms that helped usher in our human-dominated age.

The drama is about genius, hubris, and error, both individual and collective.

The film is based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s scholarly 2005 biography, “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.”

The film, which was written and directed by Christopher Nolan, extensively references the book as it examines Oppenheimer’s life and career, particularly his involvement in the Manhattan Project, also known as the Manhattan Engineer District.

Pacific War

He was the head of a covert weapons laboratory established in a nearly barren area of Los Alamos, New Mexico, where he and many other brilliant scientists of the time struggled to figure out how to use nuclear reactions to create weapons that could instantly kill tens of thousands of people and end the Pacific War.

In addition to defining Oppenheimer’s legacy, the atomic bomb and its effects also shaped this movie. Nolan delves deeply and extensively into the bomb’s construction, a process that is both intriguing and horrifying, but he refrains from reenacting the attacks; there are no photos from the documentary showing the dead or expansive views of burned cities, nor does he make any morally dubious choices.

The Horror of Bombings

The picture is permeated with the horror of the bombings, the extent of the suffering they inflicted, and the ensuing armaments race. While “Oppenheimer” is a very captivating picture and a remarkable formal and intellectual achievement, Nolan’s filmmaking ultimately serves the history it depicts.

The narrative follows Oppenheimer, who is portrayed by Cillian Murphy with a feverish intensity, as he matures through several decades, beginning with him as a young adult in the 1920s and ending when his hair turns gray.

The movie discusses his work on the bomb, the scandals that followed him, the anti-Communist attacks that almost brought him down, and the friendships and romantic relationships that both supported and disturbed him, among other personal and professional highlights.

The Affair

After having an affair with the fiery Florence Pugh as Jean Tatlock, a political firebrand, he marries Kitty Harrison (Emily Blunt) in a slow-moving sequence of events. Kitty brings their second kid with her when they move to Los Alamos.

Nolan, who has long embraced the flexibility of the film medium, has given the intricate, event-filled plot a complex framework that he breaks up into pieces that disclose more about it. Most have vibrant colors, while a few have stark black and white contrasts. The way these parts are placed creates a shape reminiscent of the double helix of DNA when they coil together in strands.

Fission and Fusion

He labels the movie with the terms “fission,” which means “a splitting into parts,” and “fusion,” which means “a merging of elements,” to indicate his premise. Because Nolan is Nolan, he further confuses the movie by repeatedly kinking up the overall chronology—it is a lot.

Additionally, Nolan doesn’t build the plot gradually; instead, he throws you into Oppenheimer’s life at random, presenting you with vivid scenes of him at various points in time. The younger Oppie (as his close friends call him) and the attentive older Oppie flash on screen in quick succession until the plot momentarily shifts to the 1920s, where the character is a troubled student plagued by flaming, apocalyptic visions.

He reads T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” puts a needle in Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” and stands in front of a Picasso picture, all of which define works from a period when physics folded time and space into space-time. He also suffers.

As Nolan completes this cubistic image, he crosses and recrosses continents and introduces a plethora of characters, one of whom is physicist Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), who was involved in the Manhattan Project.

Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., and Gary Oldman

The film maintains its quick pace and fragmented storyline. Several of the movie’s well-known actors, like Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., and Gary Oldman, are overly prominent. It took me some time to come to terms with Benny Safdie’s casting as theoretical scientist Edward Teller, dubbed the “father of the hydrogen bomb,” and I’m still not sure why Rami Malek appears in a little role other than the fact that he’s another well-known commodity.

The world becomes clearer as Oppenheimer does. He studies quantum physics in Germany in the 1920s; the following ten years, he teaches at Berkeley, mentoring other bright young things and establishing a center for quantum physics research.

Oppenheimer and Einstein

Einstein presented his theory of general relativity in 1915, so Nolan captures the intellectual excitement of the time. As you might imagine, there is a lot of scientific debate and chalkboards full of confusing calculations, most of which Nolan interprets rather easily. Feeling the kinetic energy of intellectual exchange firsthand is one of the film’s delights.

Invasion of Poland

The news of Germany’s invasion of Poland causes Oppenheimer’s life to take a sharp turn while he is attending Berkeley. By then, he has gotten to know Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett), a physicist who is crucial to the Manhattan Project and built the cyclotron, a particle accelerator.

Additionally, Oppenheimer meets Leslie Groves (a very good Damon) at Berkeley, who appoints him as director of Los Alamos despite his support for leftist causes, including the fight against fascism during the Spanish Civil War, and some of his associations, such as those with members of the Communist Party like his brother Frank (Dylan Arnold).

One of the few modern directors working at this high level both technically and thematically is Christopher Nolan. In order to achieve a sense of cinematic monumentality, Nolan, together with his excellent cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, filmed in 65-millimeter film (which is projected in 70-millimeter).

Oppenheimer and Dunkirk

When his spectacle proves to be more substantial and coherent than his plot, the effects may be absorbing, but occasionally clobbering. However, in “Oppenheimer,” just as in “Dunkirk” (2017), he employs the format to communicate the scope of a momentous occasion; in this instance, it also reduces the space between you and Oppenheimer, whose face simultaneously functions as a panorama and a mirror.

Every frame of the movie displays technical mastery, yet this is technical mastery without of self-aggrandizement. Even well-meaning filmmakers might become ostentatious when dealing with large issues; this can cause them to overshadow the history they are trying to portray accurately. By adamantly placing Oppenheimer inside a broader framework, particularly with the black-and-white sections, Nolan avoids that trap.

Lewis Strauss

The first part centers on the politically driven 1954 security clearance hearing, which ruined his reputation due to a witch hunt; the second part covers the 1959 confirmation of Lewis Strauss, a former chairman of the US Atomic Energy Commission and potential cabinet nominee (played by a captivating, nearly unrecognizable Downey).

Nolan creates a dialectical synthesis by fusing sequences from the hearing and the confirmation. Strauss’s involvement in the hearing and his friendship with Oppenheimer directly influenced the outcome of the confirmation.

The Methodology

Among the best illustrations of this methodology is the severe, existential perspective that Oppenheimer and other Jewish project scientists—a few of them were exiles from Nazi Germany—had on their work. Nevertheless, Oppenheimer’s brilliance, qualifications, reputation abroad, and devotion to the US government during the war cannot protect him from political scheming, small-minded people’s conceit, and the overt antisemitism of the Red Scare.